During the April, 2016 presidential primaries, Midwesterners’ warm and welcoming personalities rose to the forefront of national attention. Madison residents boast that their town’s unique flavor of “Wisconsin Nice,” makes the City of Four Lakes an especially friendly place to live and work. Now the “76 square miles surrounded by reality” making up the Madison Metropolitan area has also received recognition for being one of the best cities in America for cyclists.

The Bicycle League of America regards five cities above all others as the best places to bike in the United States, awarding them “platinum-level” distinction: Madison, Wisconsin; Boulder, Colorado; Davis, California; Portland, Oregon; and Fort Collins; Colorado. Madison was the most recent addition to the platinum club, earning the distinction in autumn, 2015, after seven long years of effort on the part of Madison Common Council to “make Madison the best place in the country to bicycle.”

Responding to the announcement in a statement to The Wisconsin State Journal, Madison mayor Paul Soglin said,

“What a great recognition for the incredible bike paths, bike lanes, our relationship with Trek and B Cycle, cycling amenities and the welcoming nature of our city toward cyclists.”

Wisconsin has long been a bicycle bastion—post-bellum pedalers took to their velocipedes on state-funded trails as early as 1890. Bikes have gained functionality and lost weight since the turn of the century thanks, in part, to innovations from the Badger State. One of the leading manufacturers of bicycles worldwide, Trek Corporation, still maintains the Waterloo, Wisconsin headquarters where Dick Burke and Bevil Hogg first started selling their hand-manufactured, $200 steel touring frames.

Despite Madison’s bike-friendly heritage, the path to platinum was not always smooth riding.

“When the City of Madison joined with local bike enthusiasts to begin the process to achieve platinum status, many people thought it was an unreachable goal,” mayor Paul Soglin said in a statement.

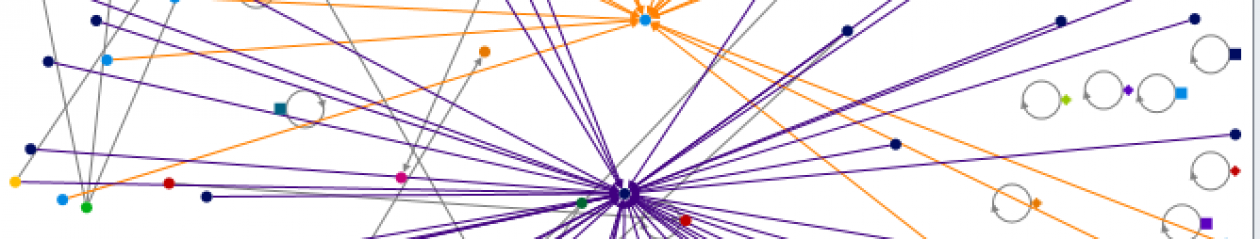

Mayor Soglin’s pessimism may have come from comparisons between Madison and the other municipalities that achieved platinum status. Davis (platinum-level since 2005) boasts bike-commuting rates reaching as high as 23.2% according to 2014 census data (Bike and car-commuting rates, teal bars). Madison trails behind every other platinum-level bike-friendly community, with rates seemingly stuck below 6%. Additionally, although fewer Madison residents drive to work compared to the national average, locals were one and a quarter times more likely to car-commute than people living in Boulder (Bike and car-commuting rates, brown bars).

Madison’s meager bike-commuting rates compared to the other platinum-level cities could come from factors beyond the City Council’s control. Although Wisconsin residents are famously warm and friendly, Wisconsin winters can be brutally cold. Frigid wind and lake-induced winter mix of sleet and snow can drive all but the most determined bicyclists to find warmer ways to get to work. Madison endured a particularly punishing winter in 2014, when a Polar Vortex brought 24 straight days of below freezing temperatures to the city on the isthmus (Longest freezing spells, orange bars and cool colors).

Although citizens of Boulder, and Fort Collins, Colorado, also observe the mercury in their thermometers plunge below the 0 degrees C mark relatively frequently, neither endured more than eight days in a row below freezing during 2014. Additionally, both municipalities bask in over 250 days of sunshine per year (Percentage sunny days, orange bars and size of circles). Davis, California narrowly edges out Boulder and Fort Collins for brightest bike-friendly community, with clear skies 78% of the year. Madison’s skies are more similar to Portland’s; both cities hovered around 50% sunny days. Even with such dismal weather, Madison’s citizens still take advantage of the city’s extensive network of bike trails.

That network continues to expand, under the oversight of the Platinum Biking City Planning Committee. Madison Engineering has improved existing bicycle infrastructure, and laid down new commuter paths and protected bike lanes throughout the metropolitan area. Between 2010 and 2013 the percent of houses with access to Madison’s bike network (defined as located within one half of one mile to the nearest dedicated bike-route) nearly doubled, reaching a height of 94%. Although construction projects to improve the bicycle network temporarily closed down segments of trail in 2014, thus reducing the percentage of coverage to 80%, the vast majority of Madison residents could, in theory, access the bike trails relatively easily (Bike network access, height of marks).

Yearly average cyclist counts at University Avenue at Mills Street, the Southwest Commuter Path at Regent Street and Wingra Creek suggest that people do take advantage of their access to Madison’s bike network (Bike network access, color of marks).

Counter-intuitively, more cyclists on the trails did not correspond to fewer cars on the roads; average weekday arterial traffic volume remained relatively constant between 2010 and 2014 (Bike network access and traffic, red line).

Bicycle advocates sometimes face opposition from drivers because limited infrastructure budgets demand that every project benefit broad sectors of the population. Although putting money into bike paths may not make car commuting more pleasant, these projects do offer tangible benefits and make the roads safer places. The total number of cycling crashes decreases between 2010 and 2014 (Bike network access and crashes, orange line).

Crashes at the city’s most problematic street crossings, intersections where bikes and cars collided multiple times, dropped by half between 2010 and 2014, mostly due to fewer crashes in the outlying areas to the south (The most dangerous intersections for bicyclists).

Drivers commonly complain that cyclists have no regard for the rules of the road. Although collecting data for every single minor, incidental violation, such as failure to yield or rolling stops would represent an impossible undertaking, Madison Police Department does maintain records of reported traffic incidents. Examining the official descriptions of car-versus-bicycle crashes from 2013-2015 reveals a near equal mix of drivers and cyclists at fault (What happens when bikes and cars collide? mouse overmarks on map to read Police reports). Although assigning blame can be cathartic, the consequences of bike-car collisions reveal a chilling reality: cyclists, including children, are much more likely to sustain sometimes serious injuries, or even die, following an encounter with a vehicle.

Decreasing the amount of these devastating encounters will be vital moving forward, as Madison has committed to maintain its status as a platinum-level bicycle-friendly community, and even strive to achieve further distinction by attaining diamond-certification from the League of American Bicyclists. To achieve this lofty goal the city needs to increase overall ridership and improve on existing efforts to make Madison a great place to bike. The road ahead may not be easy—Portland, a city with a friendlier climate, similar income demographics and higher bike commuting rates—is in danger of losing platinum-level status due to a recent string of traffic fatalities. Madison must ensure that its streets are safe for cyclists, and increase the numbers of riders on the road by identifying new populations of potential bikers.

One group that displays disproportionately low rates of bike commuting is women. Even in Davis, the country’s original platinum-level community, with 23% of the population riding to work overall, 27% of men and only 19% of women choose to go by bike. In Madison only 3.2% of women ride their bikes to work compared to 7.2% of men (Gender differences, compare pink versus blue bars).

The gender divide doesn’t hold true for all modes of transportation, nor all cities. Nationally, men and women drive to work with roughly equal frequency. Roughly 10 percent of both Men and women walk to workin Madison, giving the city the highest rate of on-foot commuting among all of the platinum-level bike-friendly communities, and roughly three times the national average.

Strikingly, women are significantly more likely to drive than men in Davis, Boulder and Portland. Women in Portland and Madison also ride public transportation more frequently than men, whereas the opposite holds true for Davis. Overall, Davis’ efforts to promote alternatives to driving appear to reach mainly men, whereas other cities more closely mirror national differences between genders.

Achieving gender parity in bike commuting will make the nation more bicycle friendly and inclusive overall. Locally, reaching out to women walkers could increase ridership in Madison. Wisconsin winters may be brutal, but the cold temperatures apparently don’t deter pedestrian commuters from braving the great outdoors.

Obstacles preventing women from biking to work likely stem from deeper societal sexism, which will be difficult to stamp out. However, the bike-riding community could benefit from self-reflection to identify exclusionary behavior, either implicit or explicit. Platinum-level bike-friendly communities skew overwhelmingly young, white, and wealthy, which is why bike-advocates and residents alike should strive to be inclusive and consider diverse perspectives.

Davis, Fort Collins, Madison, Boulder, and Portland are all homes to large public universities. The preponderance of students within the city limits likely contributes to the trend for these communities to undercut the national median population age by up to a dozen years, in the case of Davis, California (Income, age, and racial demographics among platinum level bike-friendly communities).

Large universities not only bring students into town, they can also act as magnets for high-paying jobs, which is consistent with the high median family incomes observed in most platinum-level bicycle-friendly communities. Compared to the national median family income, Madison residents take home almost $8,000 more per year than typical citizens. People living in Boulder, Colorado earn more than double the national median. With a median income of $50,271, Portland, Orgeon is the only bicycle-friendly community comparable to the rest of the country in terms of family earnings (Income, age, and racial demographics among platinum level bike-friendly communities).

The platinum-level cities are less diverse than the nation as a whole. In addition to being the wealthiest of the bunch, Boulder, Colorado has the highest proportion of white residents, 26% greater than the national average of 62%. Davis is the most diverse, according to estimates from the U.S. Census bureau.

The demographic data shouldn’t downplay the efforts of dedicated individuals in each town who devoted significant amounts of resources to achieve the distinction. However, if the League of American Bicyclists truly wishes to bring about a bike-friendly nation, they need to engage with all citizens, not just college students riding 10 minutes to and from class.

Americans, on average, travel 26 minutes to and from work (Percentage opting for mode of transportation versus mean commute time, x-axis). Almost one sixth of Americans spend longer than 45 minutes commuting each direction. Workers living in platinum-level bicycle friendly communities tend to have shorter commutes than the average American (Distributions of most common commute times, blue colors). Portland workers’ commute times are closest to the national averages, and Davis residents spend the least amount of time in transit. Typical Madison residents spend just 20 minutes getting to and from work, and over half of Madison workers spend less than 20 minutes commuting.

At least in bike-friendly communities, the length of people’s commute seems unrelated to their preferred mode of transportation (Percentage opting for mode of transportation versus mean commute time, toggle between biking, driving, public transit, and walking using buttons). Convincing committed car-commuters to opt for carbon-neutral transportation in place of their 10 minute morning drive might be challenging. But the data also indicate that some individuals travel for significant time each day on foot or by bike, suggesting that structural factors, like distance to work, alone aren’t an insurmountable barrier to a bike-friendly America.

Certified bike-friendly communities exist in all 50 states—Wisconsin is home to 16. Even if all of these cities haven’t reached platinum-level status, devoted commuter paths, well-maintained pavement, and protected bike lanes on busy roads all help promote two-wheeled transit in towns across the country. Despite our nation’s vast diversity, states that support their local cycling citizens seem to also share one unifying feature: a thirst for craft-brewed beer.

The linear correlation between statewide numbers of craft breweries and bicycle-friendly communities (Bike-friendly communities versus number of craft breweries per state) could simply be an artifact of population: more people in a region will naturally increase the demand for suds and spokes. Similarly, the concentration of bike-friendly communities per capita (indicated by increasing red color in Bike friendly communities per 100,000 residents and number of craft breweries per state) disproportionately increases for sparsely populated states, like Montana. Unsurprisingly, the five highest-rated bike-friendly communities in America share reputations as being microbrew meccas, and they all happen to be located in states with especially high numbers of bike-friendly communities (indicated by by size in Barrels of craft beer per 100,000 residents and numbers of bike-friendly communities per state) that also produce large amounts of craft beer, as measured by barrels per 100,000 residents (represented by warmer colors in Barrels of craft beer per 100,000 residents and numbers of bike-friendly communities per state).

Multiple ingredients go into brewing up a bike-friendly community, and a bike-friendly nation. Infrastructure is necessary to transform metropolises into great places to bike, but sharrow-decorated streets alone aren’t sufficient. Even the best causeways can languish empty and unused if bikers face hostile environments. More importantly, few people will take to the saddle if they perceive bikers as hostile.

Because platinum-level bicycle-friendly communities skew younger, richer, and whiter than the rest of the country, bike advocacy groups should take special care to engage with people of diverse backgrounds in their efforts. Bringing multiple perspectives together around the same table could help reach a broader population of potential bikers all across the nation.

Especially if everybody sat down together over a craft-brewed beer.