Crime On UW-Madison’s Campus

Crime on College Campuses: The Big Picture

UW-Madison has experienced increasingly stricter rules and regulations at campus events that normally involve drinking from the UWPD and Madison Police. These restrictions follow dangerous Mifflin Street Block Parties that resulted in stabbings, Halloween celebrations that left students dangerously intoxicated, and football games that brought too many students to detox. These celebrations obviously elicit many underage drinking and public intoxication tickets. But, other, more severe crimes have also been committed at these events. The media coverage that follows them portrays the events as if they are the only times during the year when crime is routinely committed at UW.

But are these events the only occasions in which students are the targets of crime? Crime must also exist on campus beyond these certain times of the year. This conundrum led me to ask: what crimes are UW-Madison students most often subjected to throughout the year?

To address this question, I used the City of Madison’s open source data. The data set includes all of the police calls that were made to the Madison Police Department from January of 2012 to February 2016. Additionally, the data only includes the top 25 reported crimes from 2012 to 2016 and excludes nonviolent, non-intrusive crimes. Although the data is extensive and thorough, it lacks information from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Police Department (UWPD). But, the UWPD’s data is limited to calls made on campus property, in residence halls, and in campus buildings; the City of Madison’s data provides insights into which crimes are most often reported by students and residents who live on or near campus, including calls from off-campus housing and bars.

This data cannot conclude if crimes are rising on campus because the data is only limited to four years, and crime in Madison varies per year. Between 2011 and 2012, the rate of crime on UW-Madison campus property rose by 43.05% from 2,058 reported cases of crime to 2,944. But, between 2012 and 2013, crime only rose by 5.60% from 2,944 to 3,109 reported crimes. Although crime rates differ per year, students should be aware of the scope of crime that exists within UW’s campus to prevent themselves from becoming victims to it.

UW students are subject to a variety of different crimes throughout the year, varying in severity and frequency. Months with popular drinking events on campus tend to have higher amounts of crime. For example, during the end of the semester and graduation in May, there is a spike in theft, trespassing, and residential burglary. October generally has more thefts and liquor law violations than other months as well; this trend can most likely be attributed to Freakfest and Halloween festivities.

Additionally, certain crimes stray from the aforementioned spikes. Fight calls were only reported once per month between January 2013 and January 2014, followed by a spike in calls during May 2015. Similarly, aggravated battery calls―or battery in which the perpetrator intends to or does cause serious harm to the victim, normally with a deadly weapon―spiked in July of 2012 to 10 calls, dropped to one call per month from December 2012 to March 2015, and then fell to zero afterwards.

From these consistent spikes and independent patterns, it becomes clear that crime in Madison is difficult to analyze. Assuming that most crimes are not committed in conjunction with each other, it is more important to look at a certain crime’s pattern throughout the past three years instead of crime as a whole.

Theft, trespassing, liquor law violations, unwanted person, and damage to property calls are the top five most common crimes within UW-Madison according to the Madison Police’s data. Violent crimes are not at the top of the list―the first violent crime on the list is battery, with 332 police calls, accounting for 5.21% of the top 25 crimes committed in and around UW-Madison. Only three violent crimes even make the top 25 reported crimes: battery, sexual assault, and aggravated battery.

But, a lack of violent crime does not mean students cannot be personally affected by criminal activity. Petty crimes can also subject UW students to physical and financial danger, making them dangerous to the well-being of students on campus. Theft is the most frequently committed crime, according to this data set, with 947 reported cases of stolen possessions. Under the same category, 428 reports of damaged property and 202 reports of stolen bicycles were reported over the past three years. Although these crimes do not put students in any physical danger, being the victim of any crime can affect a person’s stress levels and mental health.

Nonviolent crimes like theft are reported much more frequently than violent crimes like aggravated assault; given that certain crimes happen more frequently than others, it is also important to recognize where these crimes are consistently reported. This data set includes all calls to the Madison Police Department, which makes knowing whether or not the reporter was a student or resident impossible. But, if a crime occurs in or around campus, it is likely that a student could be the subject or reporter of that crime.

The area around State Street and University Avenue has the most reported crimes; since 2012, there have been 756 police calls made from the intersection of North Broom Street and West Gilman Street. Additionally, there have been 364 police calls made from the intersection of North Frances Street and University Avenue. South Park Street and the South Orchard Street off-campus living area are also hubs for reported crimes. The amount of calls does not mean that a certain location is necessarily dangerous, though. For example, the intersection of North Bassett Street and West Johnson Street only has 55 total reported crimes, but those crimes are theft, residential burglary, domestic disturbance, battery, and arrested person. Other locations on campus have many more reports, but with less severe crimes. Still, it is still alarming that hundreds of crimes are reported annually at these popular areas.

Regardless of where the crimes are committed, the amount of crime that exists on campus is surprising, but not alarming. Crime exists on every college campus and city, which makes knowing which crimes are most prevalent in different locations crucial for citizens to avoid being subjugated to them. Theft, trespassing, and liquor law violations are the most frequently reported crimes, and crimes occur most often around State Street, the South Orchard off-campus housing area, and South Park Street. All except four of the top 25 crimes are nonviolent, which is a good indicator of UW-Madison’s overall safety as a campus. Still, each of these crimes poses a threat to students’ physical or mental health.

Sexual Assault on Campus: A Snapshot

One crime that is physically obtrusive, emotionally damaging, and prevalent on campus is sexual assault. The topic has been covered through a controversial, misreported Rolling Stones article about campus rape, a Vox story about how college sexual assault affects all women, a Slate article covering a popular anti-sexual assault campaign, and a New York Times piece concerning the “War on Campus Sexual Assault.” Many other news stories also exist about the topic.

UW-Madison is one of the colleges actively being reported on by media outlets. The most recent reportings follow the release of an Association of American Universities’ Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct. The AAU released the results from the UW-Madison survey on September 22, 2015 that found 27.6% of undergraduate female students reported non-consensual penetration or sexual touching. Chancellor Blank responded to the survey immediately after the results were released, stating, “Every student has the right to be safe. Far too many sexual assaults are still happening at UW and at campuses across the country.”

After exploring the City of Madison’s data to analyze crime at UW, I asked a secondary question to address the increased amount of reportings about sexual assault on campus and the AAU survey: does the City of Madison’s data set align with the media’s reporting of sexual assaults?

The media’s rising amount of reports does not indicate a rising amount of sexual assaults. Yet, sexual assaults are a national university problem, and Madison is not excluded from the list of problematic campuses.

At least one sexual assault has been reported every month for the past 25 months. From January 2012 to January 2013, there was at least one sexual assault on or around campus each month. From February 2014 to March 2015, there were at least two per month. From April 2015 to February 2016, there were at least three sexual assaults per month. Additionally, this data does not include sexual assaults reported to the UWPD or unreported assaults. If this set included these additional data, the number of sexual assaults per month would most likely rise dramatically. Consequently, this data set aligns with the media’s reporting about sexual assaults and the AAU’s survey.

This small snapshot of sexual assaults at UW-Madison over the past four years, which does not include the UWPD’s reports or unreported cases, shows that sexual assault is a common, monthly occurrence at UW. But, UW-Madison has been openly spreading news about how they are working to “start a conversation” on campus in order to prevent sexual assaults in response to the AAU survey. Some students even started an organization called Men Against Sexual Assault to prevent the crime from happening on campus.

But, this is not the first time campus has addressed its sexual assault problem. A 2002 UW News article titled “Sexual assault prevention work expands” covers how the university was working to treat its sexual assault problem, including how a campus-wide survey was conducted to test the campus climate. In response, students created a new organization: Men Opposing Sexual Assault.

An article released by UW News on March 9, 2009 begins with, “In light of the recent attention to the issue of sexual assault, Berquam plans to discuss how the entire campus can join together to address the issue and ways that campus response and resources can be improved.” The article also explains how the problem should be addressed by campus as a whole.

On October 22, 2012, UW News released an article as a response to the Daily Cardinal’s letter from a UW-Madison graduate that outlined her experience with sexual assault as an undergraduate. Dean Lori Berquam responded, stating, “We’re deeply saddened to learn of her experience and want to explain how we’re working to end sexual violence on the UW-Madison campus.”

The parallels between these stories show UW’s routine response to sexual assault. Every April, UW raises awareness about campus’ sexual assault issue during Sexual Assault Awareness Month. Dean Berquam addresses the problem as campus-wide, and states how the university is working to solve the problem.

From this data and the news stories about sexual assault at UW-Madison, it becomes clear that addressing sexual assault on campus is difficult. But, UW’s systemic approach to the problem is inefficient and alarming. Responding to sexual assault in a routine and stale way is not the solution, and UW has been “starting a conversation” about sexual assault on campus since the early 2000s. Sexual assault on campus has persistently been an issue, and UW needs to address it in a more effective way.

Looking Forward: A More Transparent Campus

Although the university’s attempts to stop sexual assault on campus have been weak and ineffective, UW-Madison is at least becoming more transparent about crime on campus. In compliance with Title IX, whenever a sexual assault occurs on campus, the UWPD sends out a campus-wide email explaining the incident, suspects, and other details about the investigation.

Additionally, UW is taking initiative beyond its legal obligations to promote transparency about crime that occurs on campus grounds. The UWPD have a WiscAlert program that provides information about active emergency situations on campus that require immediate attention. They also provide Badger Watch, a campus crime prevention program that gives volunteers skills to identify, recognize, and report crimes.

The University of Wisconsin-Madison has also implemented programs to prevent sexual assault specifically through the Tonight and Alcohol Edu Programs. These programs are required for freshmen and transfer students, and concern sexual assault, consent, dating violence, binge drinking, and alcoholism.

Crime will continue to exist on and off of UW’s campus regardless of the University’s attempts to stop it. But, the university does need to find a more appropriate way to prevent sexual assaults on campus beyond sending out the same message for over ten years. Fortunately, in the recent past, UW has created mandatory sexual assault prevention programs for freshmen and implemented communication standards that promote transparency on campus. Regardless of whether or not these programs are effective, they do indicate that UW-Madison is slowly taking action to create a brighter future for the next generation of Badgers.

Commentary on Visualization Package

Strategic Data Selection & Cleaning Process

The data that I chose for this product is from data.cityofmadison.com. It includes all of the police calls made since January 1st, 2012. The original data set is titled “Madison Police Calls for Service” and includes the incident number, description of the incident, address of the caller by the 100 block, and the date and time that the call was received.

The original intention of this piece was to use the AAU survey raw data to create visualizations about sexual assault on campus. But, for privacy reasons, the AAU will not release its data. I pivoted my approach and decided to look at crime as a whole on UW-Madison’s campus. This pivot led me to seek the UW Police Department’s data.

The UW Police Department (UWPD) does not give their data to the public without a processed request. Also, the UWPD charges for print copies, making it a less favorable choice. But, given that the UWPD data would only cover crimes that occurred on campus property, such as buildings and dormitories, the data set would not have conveyed an accurate representation of the types of crime UW students face.

Fortunately, the city of Madison’s data is readily available online, and it avoids the problem of only including data that happened on campus property. Instead, this data set includes crimes committed on and around campus, like at bars, on off-campus housing, and at other popular areas for students to congregate. This data set was chosen because it is more inclusive of crime committed where students live and socialize, not just where they study.

The Madison Police have many data sets available, but some of them were flawed. One data set, titled “Map: Madison Police Calls for Service,” would have been an excellent choice for this project, but it has not been updated since August of 2014. I also knew that I would be able to extract a longitude and latitude from the Madison Police Calls for Service data set, making the aforementioned data replaceable. “Police Incident Reports” only includes fulfilled reports, and not all of the completed reports are in the data set. Instead, the “Incidents listed are selected by the Officer In Charge of each shift that may have significant public interest. Incidents listed are not inclusive of all incidents.” For these reasons, this data set was not used.

To clean the “Madison Police Calls for Service” data set, I deleted the type column and kept the description, date/time, and location columns. I then removed all of the rows that were missing a description, date, or location to make the data readable by data visualization software like Tableau. Then, I altered the date/time column so that it only included the day, month and year. Afterwards, I extracted the longitude and latitude from the address column so that the data could be used to create maps.

Once the data was cleaned, there were roughly 584,000 data points. To reduce the amount of data I was working with, I removed some of the crimes that were neither violent or property related, such as calls for information, private property parking complaint, check property, noise complaint, and safety hazard. I deleted this data because it was not relevant to the story. Additionally, I filtered the data so that only the top 25 most reported crimes were kept to make the information more digestible for readers. This slimmed the data set down considerably.

Once the data was clean, I filtered the data so that only crimes reported on UW-Madison property, near UW-Madison buildings, off-campus student housing, and at popular areas for students to socialize would be contained in the data set. These areas include State Street and its surrounding streets, Langdon Street, Regent Street, the South Orchard living area, and UW-Madison’s campus. This filter slimmed the data set down dramatically. After filtering out the unrelated incidents, my data was ready to be visualized.

Prior to analyzing my visualization choices, it is crucial to understand the limitations of this data set. Primarily, no conclusions about the amount of crime on or near campus can be concluded from this data, because it is data about police calls, not fulfilled arrests. Also, the data is missing the UWPD’s data, and does not include any calls made to the UWPD. It is also important to note that unreported crimes are not included in this data, which makes the data an inaccurate representation of reality. But, the data still effectively serves as a screenshot of crime and sexual assaults over a four year period that help validate reportings by the media.

Visualizations Commentary

Overall, the goal of my visualizations is to present an easy-to-digest package that makes the amount and frequency of crime at UW-Madison easy to understand. The color scheme of black and red was chosen because the contrast clearly distinguishes the selected crime from other crimes, and it also evokes a serious and alarming mood from the viewer. Additionally, following Alberto Cairo’s The Functional Art’s best practices, the simplicity of this color scheme aligns with human pre-attentive processing habits by showing one bright red line among the black lines. Consequently, the visualizations follow Edward Tufte’s data-ink ratio rule by appearing straightforward.

Other visualizations could have been made from the data set I selected, but I strategically made these to create an understanding about how different crimes at Madison rank against each other, when crimes occur, and where they occur on campus. My visualizations achieved this by presenting straightforward, clear visualizations that tell a story on their own while complimenting my written content.

Police Calls Over Time

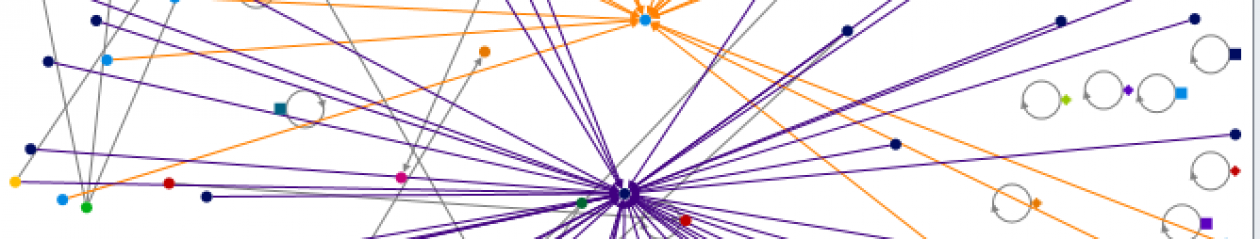

The “Police Calls Over Time” visualization gives the user more freedom to explore the relationship between certain crimes and times of year. It also builds off of prior visualizations that only included limited information about when crimes were committed. The highlighting action allows viewers to see when crimes occurred in Madison.

A line graph was chosen because it accurately shows the relationship between time and crimes. Also, it allows the viewers to see how their selected crime relates to other crimes. The graph’s interactivity allows the viewer to become more involved with the data and draw their own conclusions. Finally, this visualization adheres to Tufte’s best practices by delivering a very simple, but deep, visualization. It also takes into account pre-attentive processing by giving the viewer an opportunity to highlight a crime they wish to analyze.

Unfortunately, this graph is limited by time, since the only available data is from January 2012 to February 2016. This limit prevents any meaningful, overarching trends from being concluded by the data, albeit some spikes can still be seen. For example, there is always a small spike in October, even though that spike only occurred four times.

Choose a Crime Over Time

This visualization package is intended to allow viewers to explore the different types of crime in Madison as a whole since 2012. The visualizations are clean and straightforward, but promote some interactivity by allowing the “highlighting” action to show where a crime ranks among other crimes. These two graphs generally follow Stephen Few’s best practices of data visualizations by representing quantities accurately, making them easy to compare, and making values easy to rank. Additionally, the pie chart makes the package more memorable by adding another layer of depth to the visualization.

This visualization was made simple strategically. The bar chart makes the frequency of reported crimes easy to understand, and the pie graph is another way to justify how one crime’s frequency relates to the rest.

These graphs have some limitations, though. Although the bar chart conveys which crime has been reported the most since 2012, it does not show how the crimes vary per month, or if one particularly criminal month skewed the rest.

Police Call Locations

This visualization is intended to make the data more relatable and useful to UW students by showing the geographic locations of each of the calls. It also promotes interactivity with the data by allowing viewers to see where and how often crimes have been committed.

The map was chosen because it personalizes the data to any UW-Madison viewer by allowing them to explore areas where they live or socialize. This follows Holmes and Neurath’s best practices of visualizations by prioritizing making visualizations easily digestible and memorable.

The graph is limited because of the location data, though. The crimes are recorded by 100 block, which means that certain crimes are chunked together, making certain blocks or intersections look like criminal hotspots even if they are not.

Sexual Assault Over Time

“Sexual Assaults Over Time” isolates sexual assault to clearly show the amount of reported sexual assaults throughout the past four years. Albeit the amount of sexual assaults is not consistent with the AAU’s survey reports, it does quantify and visualize the general idea that sexual assault is a problem on campus. This graph isolates one aspect of “Crime Over Time”, which enables cross-visualization interactivity as well.

This visualization utilizes Cairo’s best practice of adding depth to a visualization by making one-dimensional data more representative of sexual assaults in Madison. The added “step color” to the graph makes the rising number of sexual assaults clearer. The color also elicits a sense of alarm from the viewer, making the graph more engaging.

The graph’s limitations come from the lack of data. There is not enough data to convey a universal trend about sexual assaults around campus. This means that there cannot be any meaningful conclusions drawn from the visualization. The small amount of data supports the the AAU’s findings, making it a meaningful graph.